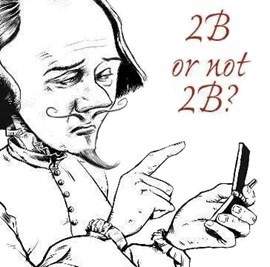

hey hw r u? bh hbu? gr8! wu? idk nm. k c u l8r. hagd. thx. np.

Seem like a normal conversation to you? If it doesn’t, you were most probably born before 1980 and you don’t text all that often. But check any adolescent or young adult’s phone and you are likely to find something very similar to the above conversation.

One of the most fascinating impacts that digital communication and smart devices have had on society over the last several years is how our speech and communication skills have been affected. It may be easy to dismiss such claims by saying that digital communication is reserved for emails and texting and it has no impact on how people communicate in the real world. A closer look, however, reveals that unfortunately is not the case.

On a very simple level, even if these short form and curt conversation styles are just reserved for emails and texting, there are still basic human norms that should govern all forms of communication. Just because two individuals are exchanging ideas through a screen, does not mean that a polite good morning or thank you can be omitted. I would never walk into someone’s office and just start detailing my list of tasks for them. I would first say hello and how are you. Then I would tell them what they must do. Why has it become the accepted norm to respond to an email by simply saying “yes” or “no, that doesn’t work”?

The effects are especially amplified in children and adolescents. Studies show that the more one engages in texting language, known as Textese, at a young age, the more one’s literacy and language development are stunted. When we communicate face to face, we are forced to use our brains to piece together letters and words into a sentence structure. The more often we do that, the better we get. The more often we type out a few short-form phrases, the more our brains become used to that level of communicating. Then we are asked to express ourselves in a meeting or in a deep conversation with our spouses. It is no wonder that we struggle to construct a coherent sentence. Cud u imagn wut my artcls wud b lk f id grn up txting?

In the late 1800’s, an invention was introduced into the Beis Medresh- a rotating, tabletop seforim holder. Someone learning in the Beis Medresh would no longer have to stand up and reach for a sefer at the other end of his table. He could now simply turn the fancy gadget and the sefer would come to him. One of the gedolim at the time protested the proliferation of these contraptions because he felt it would breed, if even in the subtlest of ways, a degree of laziness within the talmidim.

Adding in a few more letters into a text message adds approximately seven seconds, less if you have the lightning quick thumbs of the “i generation”. Including a brief greeting or cordial closing in an email may cause us to spend a few extra minutes each day sitting at our desk, but not doing so isn’t making us more efficient, it is making us lazier. It is breeding within us a perspective that the few extra strokes of my fingers are not worth the warmth and courteousness that it would portray. As subtle as it may be, the effects are there. The Baalei Mussar write that our middos are not skills that we can compartmentalize and use as needed. Rather, they are a part of us and are automatically infused into everything that we do. If we are lazy with our typing, that very same laziness will appear in other parts of our lives as well.

Perhaps the most important level of impact though is on our interactions away from the screens. Many of the Baalei Hamachshava have written about the importance of how our actions impact our thoughts and emotions. Nimshach halivavos achar hape’ulos – our hearts are drawn after our actions. We cannot assume that being abrupt and curt while responding to an email will have no effect on our view of the person I am communicating with. Even if we are not consciously aware of it, we have implanted the thought into our minds and our hearts that this person is not worth our politeness. If we were responding to someone important and official, of course we would make sure to employ the highest level of courteousness. Why should an ordinary email we respond to, and the actual person who the email is going to, be treated any less?

In his book, Virtually You, Dr. Elias Aboujaoude, Director of the Impulse Control Disorders Clinic at Stanford University School of Medicine, writes that he has seen in his practice that people blur the lines between their online personality and their offline personality. Just because they have walked away from their screens does not mean that they are leaving behind those interactions. There is only so much one can talk the talk before they start walking the walk. How we interact on our screens will affect how we interact with actual people. The more abrupt and dismissive we are within our digital communication, the more abrupt and dismissive we will be in our face to face communication.

Although it may be a major shift in one’s perspective, it really is just a few extra seconds of time. The results are tangible and will be seen and felt long after we have turned off the screens.

gg ttyl tyvm gn!