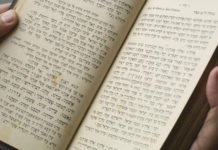

In the Torah, there is an interesting term describing the pain that Moshe saw the Jews were enduring amidst their slavery: “Va’yar B’sivlotam”- He saw their suffering. The interesting aspect of this term “sivlotam” comes from its root (svl), which is actually shared with the Hebrew word for patience which is “savlanut”. The fact that patience and suffering have the same root in the Hebrew language speaks volumes about the emotions many of us go through when we are left hanging or waiting. But why is this? Why is it so hard to have patience and what is so uncomfortable about needing to wait? In essence, waiting is a very passive action, and yet suffering seems at its core to be a very active experience. The two don’t seem to fit.

Someone recently posited to me that impatience results from feeling like there is disorder in the world when there should be order. For example: Why is this line so long? This store should really have more cashiers…Why is my plane delayed? I chose this flight because it left at my desired time….Why is it taking so long to find a spouse? I see so many people around me finding their spouses so easily…

We feel pain during the process of impatience because we feel the pressure of something that we want to control being totally out of our control. I believe that the antidote to this problem can be summed up in the famous phrase of “Let go, and let G-d”. Everything is for a reason, even waiting in a long line at a grocery store. You may not realize it at the moment (or may never realize it), but when you are stuck waiting, there really is some reason you are experiencing that wait. There are boundless examples of people, whether they were waiting for something big like to meet their spouse or something small like to catch their bus, who can report to you later that when looking back they are able to see compelling reasons why it was better for them that they had to wait. In some cases, they realize in hindsight that they weren’t properly equipped yet for the thing they were waiting for, and in some cases the fact that they waited even kept them safe from an impending disaster. There are countless stories of people who were delayed getting to work at the World Trade Center on the day of 9\11 and those delays turned out to save their lives. My husband has a friend whose relative was late for catching his spot on the Titanic and literally and thankfully missed the boat. In all these cases hindsight revealed that what seemed like impending annoyance, actually prevented them from impending disaster.

We should teach our children to entertain the idea that more mundane reasons for waiting exist as well. It could be that while they had to wait they had some extra time to think and had a novel idea about a solution to some problem they had been struggling with, or waiting gave them some time to smile at someone in line who was having a terrible day and brighten them up, etc.

If we teach our children that there is actually order in the world, even in the mundane situations, they will habitually learn the skills to calm themselves down in the not-so-mundane situations as well. When you realize that a situation requiring patience is the order set out for you right now, then you realize things haven’t gone as you’ve wanted them to in the moment for a reason. The biggest shift you can make to help kids with their patience is to teach them to accept that THEY can’t change the situation, but they can change THEMSELVES in the situation.

Patience requires delayed gratification, and thus, a large piece of this also has to do with teaching our children how to deal with delayed gratification. And believe me, this is an important one because according to the Rambam the ability to accept delayed gratification is what separates man from animals. In the late 1960’s psychologist Walter Mischel did a series of studies where he offered children a certain reward that they could get right now (for example a marshmallow) versus an even greater reward if they waited a small amount of time for it (two marshmallows). Mischel found that children who mustered the self-control to resist eating a marshmallow right away in return for two marshmallows, later on, did better in school and were more successful as adults. Part of teaching over the benefits of patience is to explain that things take work, but often the reward is greater when you work harder. Not to mention that when you have to wait for something, it feels better when you finally get it.

Statistics show that the average office worker checks their email 30 times every hour and typical mobile users check their phones more than 150 times a day. We are becoming an impatient society that wants everything now, and we need to change this tide with our children before they get lost out to sea. We have a tremendous opportunity to help our children work on their patience and view delayed gratification in such a way that their savlanut will not equal sivlotam.

* Originally published in Times of Israel